Today

I visited Leicester's "States of Independence" event - crowded as usual with small press publishers and writers (Roy Marshall, Emma Lee, etc). I bought the 2020 and 2021 "Leicester Writes Short Story Prize" Anthologies (a bargain), and "Flash Fusion" (by South Asian Writers) - the pieces I've heard from it so far sounded good.

Saturday, 22 March 2025

States of Independence, 2025

Tuesday, 18 March 2025

Sleepy heads

When Italian artists began to imitate classical statues, they copied the blank eyes. On rare occasions a statue’s eyes were closed, not blank. If the figure was in action we had to imagine that their pose showed us their dream. More commonly such statues were lying, or at least their head was sideways, like this sculpture in a village outside Cambridge.

Sophie Cave's "The Floating Heads" (Kelvingrove Museum, Glasgow) uses another trope - floating, which is more to do with dreaming, I'd guess.

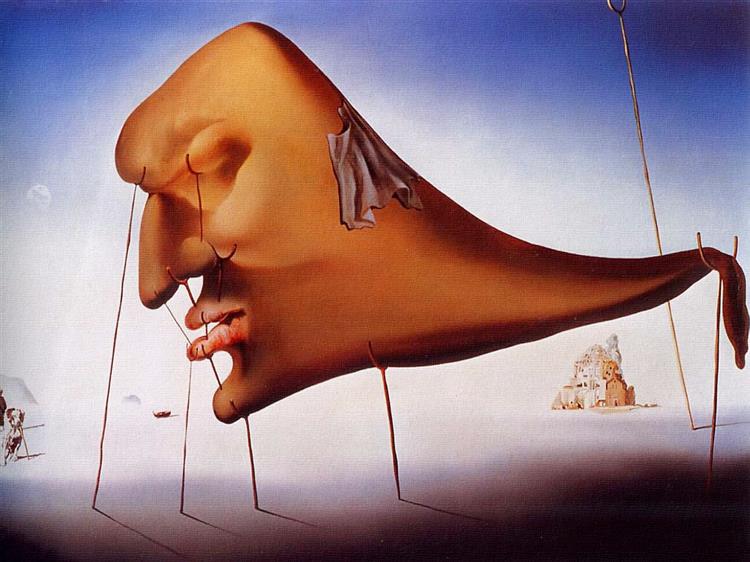

In painting, the "sleeping lover" is a genre, but that's not what Dali's depicting in "Sleep" - the head looks more like a dirigible that's lost all hope, precariously propped up. In paintings, closed eyes can mean death, but except for crucifixions statues of the dead are rare. I suppose using stone to represent death is too literal.

In painting, the "sleeping lover" is a genre, but that's not what Dali's depicting in "Sleep" - the head looks more like a dirigible that's lost all hope, precariously propped up. In paintings, closed eyes can mean death, but except for crucifixions statues of the dead are rare. I suppose using stone to represent death is too literal.

But couldn’t these figure with eyes closed be blinking? We spend about 2% of our waking life with our eyes closed. Perhaps Venus de Milo was caught in the moment of blinking so we can see her but she can’t see us. Nowadays kids sometimes paint eyes on their eyelids. Eyes, after all, are the windows of the soul. If Michelangelo had known that old statues had painted eyes, would he still have given David sculpted irises?

Tuesday, 11 March 2025

Vona Groake and Karen Solie

Tonight, taking a detour around the scaffolding in the Great Court, Trinity, I passed the busy Servery to reach the Old Combination Room - a reading by Vona Groake (St Johns writer in residence), Karen Solie (Canadian) and some student poets. Tristram Saunders (Trinity poet in residence) was the compere. A free evening with free wine. About 20 attended, which included the performers. I've read and enjoyed books by the two main poets and liked a lot of the evening's poetry - "fog makes surprising what it does not conceal", etc.

Tonight, taking a detour around the scaffolding in the Great Court, Trinity, I passed the busy Servery to reach the Old Combination Room - a reading by Vona Groake (St Johns writer in residence), Karen Solie (Canadian) and some student poets. Tristram Saunders (Trinity poet in residence) was the compere. A free evening with free wine. About 20 attended, which included the performers. I've read and enjoyed books by the two main poets and liked a lot of the evening's poetry - "fog makes surprising what it does not conceal", etc.

Last Sunday I attended an open-mic in a pub with Carrie Etter guesting. £5 and no free drink. About 40 attended. Maybe the publicity was better, or maybe the chance to read one's poems out is worth paying for. I didn't read but at least half the attendees did.

Last Sunday I attended an open-mic in a pub with Carrie Etter guesting. £5 and no free drink. About 40 attended. Maybe the publicity was better, or maybe the chance to read one's poems out is worth paying for. I didn't read but at least half the attendees did.

Friday, 7 March 2025

Character-based stories - trad vs frag

Traditional character-based stories often depend on traditional notions of self and psychology - religious ideas of Soul having morphed into Freudian concepts. Stories reach a climax when the protagonist learns/accepts something of their "true self" after removing repression or discovering/remembering some key event in their past.

Trad writers who write for/about themselves tend to measure success by how well they think they've expressed in words what's inside themselves.

Various 20th century developments have confused the situation -

- Modernism - Kafka, etc

- The trend towards interpersonal methods of growth

- Socialisation (including the effects of social media, role-play, compartmentalisation, etc)

- A distrust of unification and tidiness, and a greater tolerance for neurodivergent PoVs

- all contributing to a more fragmentary concept of self/selves and a consequent change in the character-based story template. Linear plots with epiphanies and happy endings no longer seem to model typical characters. Frag writers who write for/about themselves might measure success by how many Likes and hits one of their online personas get.

I write trad stories, but not very well. When I write frag stories, I'm conscious of omitting the very features that people would like in a trad story. I don't know if my frag stories are any better than the trad ones, but there are more outlets for them in this fragmentary publishing world.

See also

- Literature, depersonalisation and derealisation

- People who need people (a workshop about character)

- Empathy and literature

Friday, 21 February 2025

Punctuating poetry

There is

- text that uses full punctuation and no line-breaks - this is how prose is usually rendered. Some poems use this style too.

- text that uses full punctuation and line-breaks - this is how much poetry is rendered. Punctuation has various uses - "there was a movement away from rhythmical-oratorical punctuation to grammatical-logical usage between about 1580 and 1680 ... It was only in the decade of the 1840's that the grammatical-logical theories finally triumphed." (Mindele Triep). Line-breaks have several uses too. Poets often break lines at the end of clauses, which is where punctuation usually appears. This leads one to wonder if both line-breaks and punctuation are needed.

- text that uses line-breaks and no punctuation - some poetry is written like this. The amount of punctuation perhaps "reveals how writers view the balance between spoken and written language" (Baron). Or maybe the poets feels that the little black marks make the page more messy. In general, readers have little difficulty adapting to the style. All the same, I have a few objections to it

- If the poetry does need to be parsed into phrases, the structures need to be simple, otherwise readers will need to backtrack in order to work out whether ";", ":" or "," is missing, or whether the sentence is a question. But why risk the reader needing to backtrack? Why simplify the sentence structure?

- Line-breaks already have several uses. Burdening them with further duties risks overloading them, making the reading process harder

- Line-breaks seem in some poems rather a blunt instrument, used in poetry like they are in tele-prompts and adverts as an alternative to underlining.

- text that uses line-breaks and few punctuation marks - Some poets use varying amounts of indentation and between-word spacing, partly to compensate for the loss of punctuation. Commas can be replaced by between-word spaces. Full-stops can be replaced by line-breaks or paragraph breaks. Other punctuation marks (e.g. apostrophes) can be used. To me, the big white spaces can make the page look messy.

For more on punctuation see poetry punctuation

Saturday, 1 February 2025

The Friday Poem and The North - poetic language

In "The Friday Poem" (31st January 2025) Stephen Payne articulates a feeling I've not been able to put into words - how the language of some poets is slightly, persistently, non-standard. Reviewing 'The Island in the Sound' by Niall Campbell he writes that "This is immediately interesting writing. The syntax is ... reduced or disrupted ... There are a few part-rhymes ... There's the playfulness ... the verb-choices are novel: I'm sure I've never seen 'comb' as an intransitive verb meaning "to become a honeycomb" or something similar."

It's not a style I can do. I wish I could. In my self-doubting moods I feel that poets who write like this are "thinking in poetry" rather than translating into poetry. The review points out that "All these aspects of the surface language – syntax, sound effects and phrase-making – ... combine to achieve a dense and intense lyricism. ". There are radical ways for poets to make readers distrust words/language. I think this gentler style stops language being transparent (the way it tends to be in prose) without making it opaque.

"The North" (issue 68, August 2022) is subtitled "the Caring issue". It's guest-edited by Andrew McMillan and Stephanie Sy-Quia. Many of the 150+ poems baffle me, not least because of the surface language. It's probably unhelpful to quote extracts of poems out of context but I'll do it anyway -

- "First I died to my feet. Then I died to my pride"

- "I'm neither dreaming nor/ running release me slow the/ attic skylight floods so much/ rain glass grey the day ahead/ blurred a chrysanthemum/ paperweight in the palm a/ flaming porcupine" (the poem justified like prose to form a rectangle)

- "So let's asphalt cognition behind, grandly dandled by on cloud rests we lay.// One bicycle wheel is left to signal to the intermitting friendship of a butterfly:"

Lucy Allsopp has 2 side-by-side poems each entitled "Collateral". The poems are the same except that one uses "/" instead of line-breaks.

I liked "Predation" by Caitlin Young (maybe because it's micro-fiction). I think there's only one poem that used a standard form - Sarah Tait's "Brack" rigourously uses iambic pentameter, the rhyme scheme being roughly xaxa xbxb ccccdd.

Saturday, 25 January 2025

Magma, North, TLS, Poetry Review

A secondhand bookshop here is selling recent issues of the TLS, North, Magma and Poetry Review for a quid.The've all been going for a long time. The TLS (weekly) has one poem and a few reviews. The others are leading UK poetry magazines with articles and reviews. I've not read them for a year or so. I found them all a worthwhile read.

- The Times Literary Supplement (a tabloid newspaper) has reviews that always include some adverse criticism. The other mags' reviews tend to avoid saying negative things.

- Magma's issues vary according to the guest editor(s) and theme. I read the Physics issue, which wasn't one of the best. They get 5,000 submissions/issue.

- The North has so much in it that there's bound to be something to like. They have guest editors. They've rejected me the last few times I've tried. Decades ago, I used to have more luck - have they changed or have I?

- Poetry Review is the Poetry Society's magazine. If poetry is going to try to distance itself from prose, then the poems in recent Poetry Reviews show the way. Hit'n'miss, but I was pleasantly surprised. What I didn't like were the discussions, interviews and joint reviews - too much waffle and mutual praise. What's wrong with good old-fashioned essays?

In the mags I read there were 2 multi-page sequences that included illustrations - I didn't like them.

There were 3 poems that used graphics in other ways (a flowchart in Poetry Review, a boardgame in Magma, and Bingo in The North - click on the images to see clearer versions). I always want such experiments to succeed. In these examples I didn't see how the words had much to do with the form. Why does the flowchart just use rectangles? Why aren't there snakes in the game? Do the items in each row/column of the bingo card have anything in common?

My poetry pamphlet "Moving Parts" (ISBN 978-1-905939-59-6) is out now, on sale at the

My poetry pamphlet "Moving Parts" (ISBN 978-1-905939-59-6) is out now, on sale at the